The Co:UrbanLab Manifesto

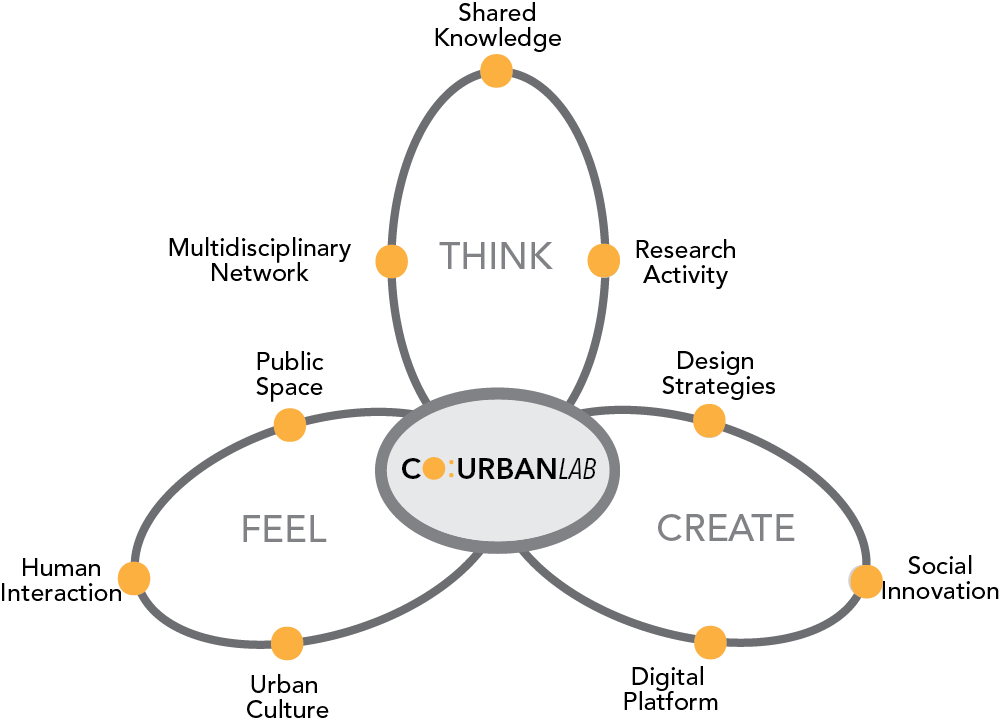

Co:UrbanLab stands for Cognitive Urban Laboratory. It is a multidisciplinary think tank thatdevelops three key concepts within the urban design, Think, Feel and Create, in order to study urban life, empower citizens and create solutions to foster social inclusion and better quality of public life in public space.

Nowadays cities are facing different problems such as social integration, human well-being, environmental issues related to climate change, resource use as well as the demand for better urban quality. In 2008 the 21th century has been identified as the “Urban Century” by UN-habitat. In addition, the United Nation adopted in 2015 the 17 Global Goals for Sustainable Development and with Goal 11 recognized the complexity of the issues related to the city and its role as a key feature towards global sustainable development. One year later, the New Urban Agenda, which was adopted in 2016 at Habitat III conference in Quito, identifies the importance of building cities that can serve as engines of prosperity and centres of cultural and social well-being while protecting the environment.

Important studies point to the urban space’s social production comprehension. However, discuss the urban space from the city perspective also demands us to better understand the relationship between public space and welfare in the cities.

At the same time, public space should be the tool to freedom of expression and spatial ownership by city dwellers as discussed by Lefebvre with the idea of the ‘right to the city’. Thus, according to Jan Gehl, it is important to pay more attention on the human dimension and the social function of the city space as a meeting place that contributes social sustainability and an open and democratic society.

The “perception” is defined as someone’s ability to notice and understand things that are not obvious to other people. This means that the perception of the city and the human dimension is the tool to investigate rhythms, rituals, customs and intangible features that define the public space identity. Thus, the perception of the city makes possible the analysis of citizen’s wishes and needs, necessary to reach their self-satisfaction. The city should become an organism capable of self-monitoring of its environment and the dwellers behaviour, creating thus a smart habitat able to engage citizens in shaping their attitudes and habits.

This is why, in this urban century, the city, public space and public life are the primary unit ofa cognitive methodology with a “people oriented” attitude, as a different way to investigate human and urban elements, which give quality to the public spaces within the city,for architects, artists, economists, geographers, sociologists, urban designers and urban planners.

Co:UrbanLab’s calls for the “the right to the city”. It explores the urbanity in an inclusive and flexible cognitive way by developing three key concepts within the urban design, they are:

T h i n k . Co:UrbanLab thinks with a wide research activity that empowers knowledge and considers the city as a dynamic urban reality with a multiple and complex combination of layers, patches and patterns, as they differ on various aspects, such as the physical and social composition or their symbolism. The intent is to juxtapose, link and overlap them in order to better understand city’s human dimension.

F e e l . Co:UrbanLab analyses, experiences, feels and reads the stimuli which come from the public realm around the world. By doing so, the Lab is able to raise awareness and increase the right of appropriation and participation of public space on urban culture through different initiatives and tools, such as art, bottom- up actions, graphic design, photography, social media, video-making.

Create. Co:UrbanLab creates solutions and tools to empower citizens in the decision-making processes. Working on different inclusive tools can lead to a participative creation of urban space based on free information technology and feedback. This practise allows dwellers to have direct voice in the production of urban space and, thanks to interactive platform, to contribute freely to its shaping.

Public space should be an international and recognized democratic common ground, where thanks to its perception is possible to compare different cultures and thus promote and foster social inclusion, better urban quality and well- being. The human dimension and all of its cognitive aspects are the results of a mixture of knowledge and practises, thus Co:UrbanLab relates to every field of urban culture and social sciences, such as:

- Agronomics;

- Anthropology;

- Architecture;

- Art;

- Cognitive Science;

- Economics;

- Geography;

- Public Policies;

- Sociology;

- Urban Design;

- Urban Planning;

This is the reason why the cognitive process is based on an interdisciplinary network of artist, activists, citizens, professionals, scholars, thinkers and it is open to establish new connections with different disciplines, organizations, professionals coming from all around the world.

| City | Multidisciplinary | Social Impact |

| Climate Change | New Urban Agenda | Social Inclusion |

| Common Good | People | Sustainable Development Goals |

| Cognitive Processes | Perception | Urban Consciusness |

| Environment | Public Life | Urban Culture |

| Governance | Public Space | Urban Regeneration |

| Greenery | Right to the City | Urban Resilience |

| Identity | Social Engagement | Well-Being |

| Intangible Heritage |

Academic

- Amin, A. & Thrift N. (2001), Reimagining the Urban, Polity Press, Cambridge.

- Bicchieri C. (2016), Norms in the Wild: how to Diagnose, Measure, and Change Social Norms, Oxford University Press, Oxford.

- Bravo, L. (2012), “Public spaces and urban beauty. The pursuit of happiness in the contemporary European city”, in Pinto da Silva, M. (ed.), EURAU12 Porto | Espaço Público e Cidade Contemporânea: Actas do 6° European symposium on Research in Architecture and Urban design, Porto, Faculdade de Arquitectura da Universidade do Porto (FAUP), 12-15 September.

- Carmona, M.; Tiesdell, S.; Heath, T.; Oc, T. (2003), Public Places – Urban Places. The Dimensions of Urban Design, Routledge, London and New York.

- Chase, J., Crawford, M., & Kaliski, J. (1999). Everyday urbanism: featuring John Chase. New York, N.Y., Monacelli Press.

- de Waal, M. (2014), The City as Interface – How new media are changing the city, Nai010 Publisher, Rotterdam.

- Gehl, J. (1971), Livet mellem husene – udeaktiviteter og udemiljøer, Arkitektens Forlag, Copenhagen (En. trans.: Life between buildings, Hoboken, Wiley John & Sons, 1987).

- Gehl, J. & Svarre, B. (2013), How to study public life, Islandpress, Washington.

- Jacobs J. (1961), The death and Life of Great American Cities, Random House, New York.

- La Cecla, F (2015), Contro l’urbanistica, Giulio Einaudi Editore, Torino (En. trans.: Against Urbanism, PM Press/Green Arcade, Oakland, 2017).

- Lefebvre, H. (1968), Le Droit à la ville,Anthropos, Paris.

- Leighton Chase, J.; Crawford, M; Kaliski, J. (2008), Everyday Urbanism, The Monacelli Press, New York.

- Mitchell, J. W. (1995), City of bits. Space, Place, and the Infobahn, The MIT press, Cambridge MA.

- Whyte, W. (1988), Rediscovering the center, Doubleday, New York. (ed University of Pennsylvania Press, Philadelphia, 2009)

- Whyte, W. H. (1980). The social life of small urban spaces. Washington, D. C.: Conservation Foundation

Non Academic

- Habitat III Secretariat, New Urban Agenda, United Nation, Ecuador

- Karssenberg, H.; Laven, J.; Glaser, M. & van’t Hoff, M. (2016), The city at eye level – Lessons for street plinths – Second and extended version, Eburon Academic Publishers, Delft.

- Lydon, M. (2012), Tactical Urbanism 2 – Short-term action|Long-term change, Street Plans, New York.

- Lang Ho, C. (2012), ‘SpontaneousIntervention: design actions for the common good”, Architect The AIA Magazine, 101, no. 8, pp. 20-26.

- Nold, C. (2009), Emotional Cartography. Technologies of the self, Wellcome Trust, Londra.

- Mikoleit, A. & Pürckhauer, M. (2011), Urban Code – 100 Lessons for understanding the city, The MIT Press, Cambridge MA.

- UN- Habitat. (2008) State of the World’s Cities 2008/2009: Harmonious Cities. Earthscan, London.

- Perec, G.(1975) Tentative d’épuisement d’un lieu perisien, Christian Bourgois èditeur, Paris

- Benjamin, W. (1963) Städtebilder, Suhrkamp Verlag, Frankfurt am Main

On sense of place, aesthetics and heritage, perception of belonging, security and livability, and aspirations for the future.

The right to the city is the right of all inhabitants, present and future, permanent and temporary to use, occupy and produce just, inclusive and sustainable cities, defends a common good essential to a full and decent life.”

Individual and collective actions designed to identify and address issues of public concern.

The way in which something is regarded, understood, or interpreted

Development that meets the needs of the present without compromising the ability of future generations to meet their own needs. Sustainable development is a holistic framework that puts together three basic pillars: economic development, social inclusion and environmental sustainability

The New Urban Agenda is the outcome document agreed upon at the Habitat III cities conference in Quito, Ecuador, in October 2016. It guides the efforts around urbanization of nations, city and regional leaders, United Nations programmes and civil society for the next 20 years.

Public space is a common good, meant to be open, democratic and inclusive; a right for everybody.

Urban Code consists of brief observations on an ambience which tries to move beyond passively looking at these scenes to encourage a way of seeing into them, - to understand the forces that shape a place, and how these forces lead to the creation of its special atmosphere.

Urban consciousness is a concept related to understanding and adapting to the conditions and norms of living in a city has become an important aspect of life quality studies.

Social Impact include all social and cultural consequences to human population of any public or private actions that alter the ways in which people live, work, play, relate to one another, organize to meet their needs, and generally cope as members of society.

The social space is a product of society; space is created by both the planners and the users through actual use as well as its representation,

Urban Resilience is the capacity of individuals, communities, institutions, businesses, and systems within a city to survive, adapt, and grow no matter what kinds of chronic stresses and acute shocks they experience.